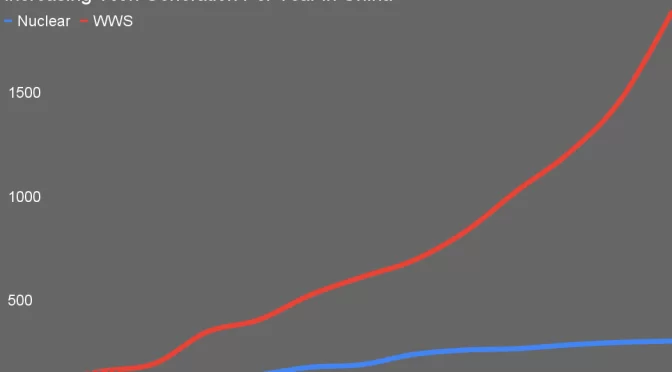

Once again, China’s nuclear program barely added any capacity, only 1.2 GW, while wind and solar between them added about 278 GW. Even with the capacity factor difference, the nuclear additions only mean about 7 TWh of new low carbon generation per year, while wind and solar between them will contributed about 427 TWh annually, over 60 times as much low carbon electricity.

As a note, there were no new hydroelectric dams commissioned in China, so that continued acceleration of deployment is solely due to wind and solar. That’s going to change when the absurdly massive Tibetan Yarlung Tsangpo river dam is commissioned, likely in the mid 2030s. That dam will generate three times the energy annually as the Three Gorges Dam, making it by far the biggest dam in the world by every measure.

A few points. First, what’s a natural experiment? It’s something which is occurring outside of a laboratory or research setting in the real world that coincidentally controls for a bunch of variables so that you can make a useful comparison. An often referenced example was of a specific region where half was without electricity for a few months. Researchers posited that the blackout region would have seen more pregnancies starting in that period, and sure enough, that’s what they found.

So why is China a natural experiment for scalability of wind and solar? Well, it controls for a bunch of variables. Both programs were national strategic energy programs run top down. I started the comparison in 2010 because the nuclear program had been running for about 15 years by then and the renewables program for five years, so both were mature enough to have worked out the growing pains.

One of the things that western nuclear proponents claim is that governments have over-regulated nuclear compared to wind and solar, and China’s regulatory regime for nuclear is clearly not the USA’s or the UK’s. They claim that fears of radiation have created massive and unfair headwinds, and China has a very different balancing act on public health and public health perceptions than the west. They claim that environmentalists have stopped nuclear development in the west, and while there are vastly more protests in China than most westerners realize, governmental strategic programs are much less susceptible to public hostility. And finally, western nuclear proponents complain that NIMBYs block nuclear expansion, and public sentiment and NIMBYism is much less powerful in China with its Confucian, much more top down governance system.

China’s central government has a 30 year track record of building massive infrastructure programs, so it’s not like it is missing any skills there. China has a nuclear weapons program, so the alignment of commercial nuclear generation with military strategic aims is in hand too. China has a strong willingness to finance strategic infrastructure with long-running state debt, so there are no headwinds there either.

Yet China can’t scale its nuclear program at all. It peaked in 2018 with 7 reactors with a capacity of 8.2 GW. For the five years since then then it’s been averaging 2.3 GW of new nuclear capacity, and last year only added 1.2 GW between a new GW scale reactor and a 200 MW small modular nuclear reactor.

So what’s going on? As I noted late in 2023, nuclear energy and free market capitalism aren’t compatible, but China isn’t capitalist, according to a lot of westerners. But it very definitely is a market and export capitalist economy, albeit with more state intervention and ownership, and the nuclear program is suffering as a result. That lone small modular reactor is a clear signal of that.

One of the conditions for success for nuclear scaling in the past and one that exists today is to limit the nuclear designs to one or two at most, and repeat building those with rigorous controls to prevent local innovation, reengineering and redesign. As many have noted, nuclear is the only industry where incremental innovation actually slows progress.

Part of that is the inability to share lessons learned across dozens of reactor builds. Part of it is the inability to develop a workforce of skilled, certified and security credentialed construction and engineering workers when lots of different nuclear designs are being deployed, each with often very different physical, operational and security concerns.

China’s nuclear program is like its wind and solar programs, which is to say that it’s building things to deploy locally and sell globally. But there just aren’t that many differences between solar panels or wind turbines, nothing compared to the variance between a Chinese-variant AP1000 reactor and a Chinese-variant EPR, both of which are in their deployed fleet. Adding yet another design in the form of the small modular reactor is just adding to the lack of focus on the part of the Chinese nuclear deployment program that is slowing it down.

Why isn’t China able to focus? Because there’s zero consensus in the world about nuclear generation design to focus on, so the local deployments are of everything future customers might buy. China built its own EPR so that it could build the UK Hinkley reactor and other European reactors, at least until increasing western paranoia arose.

Would China have been able to match the massive and accelerating wind and solar programs if it hadn’t fallen into that trap? I think it’s deeply unlikely that it would have. Wind and solar’s modularity, manufacturability and sheer Wright’s Law advantages would always have trumped nuclear.

Solar and wind power have a history of next to no cost or schedule overruns during construction globally in Professor Bent Flyvbjerg’s data set over over 16,000 projects greater than a billion USD in cost. Nuclear generation, on the other hand, has innumerable long-tailed risks that lead to significant budget and schedule overruns. Unless you control very tightly, with military discipline usually enforced by the military, nuclear programs go far over budget and schedule.

Nuclear construction risks can be managed down and cost and scheduled constrained, but it can’t be done without all of the conditions for success in place. Even China, which has successfully built vastly more infrastructure than any country in the world in a much shorter period of time, couldn’t get it right. Maybe it will figure it out one day and keep the export strategists out of the nuclear side of the energy business. But as their wind, solar, battery and HVDC exports are booming, I suspect nuclear will continue to falter.