Wind power has been defined as the conversion of wind energy into a useful form of energy which can then be used through wind turbines to make electricity, windmills for mechanical power, wind pumps for water pumping or drainage, or sails to propel ships.

In the US, the multi-bladed wind turbine atop a lattice tower made of wood or steel was, for many years, a fixture of the landscape throughout rural America as civilisation moved westwards.

This process, in many parts of the world has since been taken forward by creating large wind farms that may consist of several hundred individual wind turbines which are then connected to the electric power transmission network.

This effort is being undertaken both onshore as well as offshore. In this context, offshore wind farms are sometimes preferred as they can harness more frequent and powerful winds than are available to land-based installations and have less visual impact on the landscape in terms of aesthetics.

Construction costs are however considerably higher. Consequently, smaller onshore wind facilities are used to provide electricity to isolated locations. This is also preferred by utility companies in the western hemisphere and they increasingly buy surplus electricity produced by these smaller domestic wind turbines.

After bio-gas and solar energy, special attention is now being given to wind power, as an alternative to fossil fuels.

This is being done as economists and environmentalists agree that, as a source, it is plentiful, renewable, widely distributed, clean, produces no greenhouse gas emissions during operation and uses little land.

Any effect on the environment, if at all, is seen as being generally less problematic than those from other power sources.

It would be interesting to note here that as of 2011, 83 countries around the world are using wind power on a commercial basis.

Records also indicate that as of 2010, wind energy production had reached over 2.5 per cent of total worldwide electricity usage, growing rapidly at more than 25 per cent per annum. Analysts have also pointed out that the monetary cost per unit of energy produced is almost similar to the cost for new coal and natural gas installations.

Movement forward within the wind energy production sector has been greatly possible because of research undertaken in this sector by the United States and Germany.

The United States in particular, through its Department of Energy-funded project in 1975 which was assisted by NASA, was able to develop utility-scale wind turbines. NASA built thirteen experimental wind turbines which paved the way for much of the technology used today.

Since then, turbines have increased greatly in size with the Enercon E-126 capable of delivering up to 7.0 MW. Quality in wind turbine production has also been enhanced by Germany and Scandinavian countries in the west and by China and Japan in the east.

A scientist explained to me the other day about how wind, the movement of air across the surface of the Earth, helps the process of creating the potential for production of energy. He pointed out that the heat energy absorbed at the Earth’s surface is transferred to the air directly above it and, as warmer air is less dense than cooler air, rises above the cool air to form areas of high pressure and thus pressure differentials.

The rotation of the Earth drags the atmosphere around with it, causing turbulence. These effects combine to cause a constantly varying pattern of winds across the surface of the Earth and that leads to economically extractable power.

It is now being claimed by scientists that energy available from wind is considerably more than present human power use from all sources. It is also being suggested by Cristina Archer and Mark Z. Jacobson that there is 1700 TW of wind power at an altitude of 100 meters over land and sea. Of this, between 72 and 170 TW could be extracted in a practical and cost-competitive manner.

It is this potential that has led to the creation of many wind farms (consisting of several hundred individual wind turbines covering an extended area of tens of square miles) in different parts of the world. Many of the largest operational onshore wind farms are located in the US.

As of 2012, the Alta Wind Energy Center is the largest onshore wind farm in the world at 1020 MW, followed by the Roscoe Wind Farm (781.5 MW). Till November 2010, the Thanet Wind Farm in the UK is the largest offshore wind farm in the world at 300 MW, followed by Homs Rev II (209 MW) in Denmark.

Worldwide, there are many thousands of wind turbines operating, with a total nameplate capacity of 238,351 MW as of end 2011. The European Union alone passed some 100,000 MW nameplate capacity in September 2012, while US surpassed 50,000 MW in August 2012 and State Grid of China passed 50,000 MW the same month. World wind generation capacity has more than quadrupled between 2000 and 2006, doubling about every three years.

The United States pioneered wind farms and led the world in installed capacity in the 1980s and into the 1990s. In 1997, Germany surpassed the US in installed capacity but the US regained the top position in 2008. China has been rapidly expanding its wind installations since the late 2000s and passed the US in 2010 to become the world leader. At the end of 2011, worldwide nameplate capacity of wind-powered generators was 238 gigawatts (GW), growing by 41 GW over the preceding year.

Electricity generated from wind power can be highly variable at several different timescales: hourly, daily, or seasonally but wind is always in constant supply making it a dependable source of energy because it will never expire or become extinct. Wind power also has low ongoing costs, and a moderate capital cost. The marginal cost of wind energy once a plant is constructed is usually less than 1.0 cent per kWh.

Experts believe that as wind turbine technology improves, costs will come down even further. There are now longer and lighter wind turbine blades, improvements in turbine performance and increased power generation efficiency. In addition, wind project capital and maintenance costs have also continued to decline.

It may also be noted that the estimated average cost per unit incorporates the cost of construction of the turbine and transmission facilities, borrowed funds, return to investors (including cost of risk), estimated annual production, and other components, averaged over the projected useful life of the equipment, which may be in excess of twenty years. Consequently, 35 per cent of all new power generation built in the United States since 2005 has come from wind, more than new gas and coal plants combined, as power providers are increasingly enticed to wind as a convenient hedge against unpredictable commodity price moves.

Bangladesh scenario: In Bangladesh, renewable energy represents 1.5 per cent of the country’s total power consumption at present. Available data indicates that we have more than 1.3 million solar home systems (thanks to IDCOL and 29 other NGOs) in place and more than 45,000 bio-gas plants in use. Policy planners are using the present implementation curve to forecast that by 2020 the share of renewable energy consumption within the national matrix will reach above 10 per cent. It has also been suggested that Bangladesh will need $ 3.0 to 4.0 billion to offset the cost. Multilateral donor agencies like the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank are being approached as potential investors in this endeavour.

The Power Division has already prepared a country paper pertaining to Bangladesh’s future sustainable use of renewable energy. This has been discussed with the UNDP in response to a request by the UN Secretary General under his ‘Sustainable Energy for All’ programme. Wind energy as another potential source also needs to be brought within this equation. It should be noted that Global Wind Energy Council and Greenpeace International have carried out serious research over the past two years and they have come to the conclusion that wind power is likely to supply up to 12 per cent of global electricity by 2020, create 1.4 million new jobs and reduce CO2 emissions by more than 1.5 billion tons per year (about five times today’s level).

We have already put in place use of wind energy in our coastal area. It has been more of a trial venture based on exploiting available wind flow at heights of around 25 meters. Careful studies have since been carried out and renewable energy experts have now come to the conclusion that the existing design has to be modified and use of wind currents at heights over 50 meters addressed. Experiments already carried out in this regard have been successful.

The government needs to seriously consider what is happening elsewhere in the world, seek the appropriate advanced technology and urgently try to replicate this valuable process in our country, particularly in the rural coastal areas in the south, south-west and south-east. Additional power would generate employment opportunities, reduce dependence on diesel oil (used extensively for irrigation) and reduce poverty.

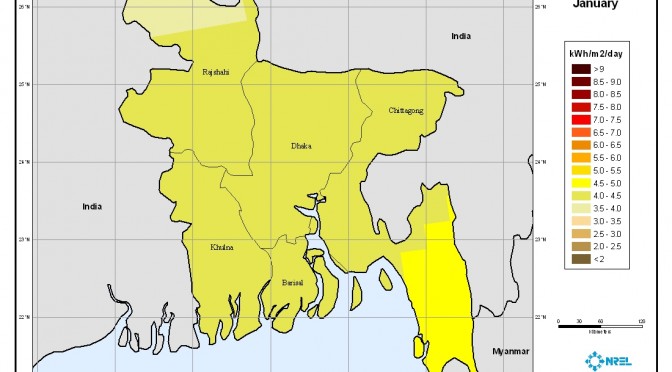

In this context, it is heartening to know that the Bangladesh Power Development Board has initiated steps through the signing of a contract with ReGen Powertech to complete a wind map for Cox’s Bazar, Kutubdia, Khepupara, Feni and Chittagong. This should enable us to find the right spot to tap into wind energy.

By Muhammad Zamir. Former Ambassador, is Chairman, Bangladesh Renewable Energy Society and an analyst specialised in foreign affair. mzamir@dhaka.net