2022 promises to be a pivotal year for the offshore wind industry. In Europe, this year is seen as the start of a period in which the annually installed generation capacity will grow year on year to meet the ambitious European Union energy targets. In the U.S., 2022 marks the year in which construction starts on the first large-scale offshore wind farm, initiating an ambitious but achievable growth path to reach the U.S.’s goal of 30 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030. Already, the scale of planned offshore wind developments is proving to be a challenge with regards to transporting the offshore wind power onshore and to the consumer. Suitable onshore points of interconnection are not limitless, and in some cases the existing onshore grid requires substantial upgrades. Cable corridors and cable landing points may sometimes need to traverse environmentally sensitive or urban areas. And the local U.S. supply chain is still limited, but will grow over time as more projects break ground.

To overcome these challenges, several solutions are beginning to find widespread application in Europe, and hold significant promise for the growing U.S. offshore wind market: 1. adopting multi-terminal HVDC transmission technology; 2. multi-purpose infrastructure; and 3. coordinating the offshore transmission development.

1. HVDC technology

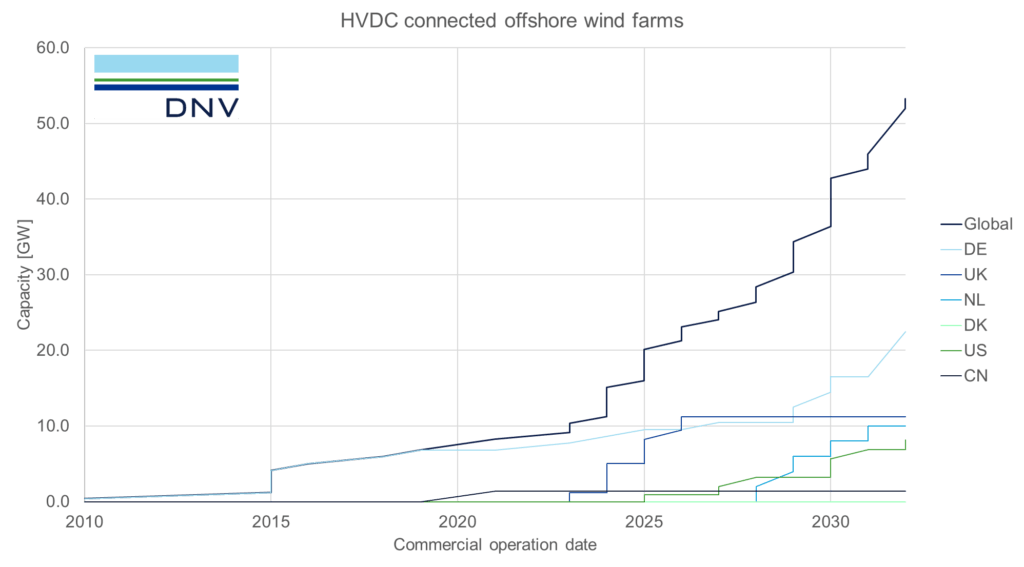

Meshed offshore HVDC transmission grids are seen as one of the solutions to tackle the challenge of grid integration from the exponentially growing deployment of renewable energy resources. With a significantly higher capacity than AC cables, HVDC connections can reduce the number of cables that are necessary by bundling the outputs of multiple offshore wind farms into a single high-capacity export link. HVDC technology enables economic transmission with low environmental and visual impact for hundreds to even thousands of miles, enabling delivery of offshore wind power further inland, closer to load centers, and also enabling connections between different states and remote renewable energy resources. For this reason, the uptake of HVDC systems for offshore wind export is growing rapidly worldwide and the total installed capacity is expected to increase five-fold over the next 10 years, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Cumulative capacity of installed and planned HVDC connected offshore wind farms worldwide

2. Multi-purpose infrastructure

By combining the functions of offshore wind export and energy trade between different points of interconnection or states into one interconnected multi-terminal HVDC grid, so-called hybrid or multi-purpose infrastructure can be created. This can reduce the total amount of infrastructure needed—and hence the cost and environmental impact. At the same time the infrastructure utilization is maximized, improving the return on investment, which ultimately can result in reduced consumer bills. Meshed HVDC grids are a special type of multi-terminal HVDC grids, in which alternative redundant transmission paths can be utilized in case of equipment outages, to safeguard the reliability of the energy supply.

3. Coordinated planning

By building out offshore infrastructure as part of a coordinated transmission planning process, offshore wind farm developers would no longer have to build their own transmission links. If properly implemented, this would lower the barriers to entry and stimulate a competition on factors other than onshore interconnection rights. Realizing such cross-jurisdiction transmission grids requires a coordinated approach with aligned planning horizons. Coordination is required vertically between federal, RTO, state, and county planning and permitting authorities, as well as horizontally between different states’ public utility commissions, RTOs/ISOs, and planning and permitting authorities. Pragmatic and functional communication channels and platforms between these parties and development of common ground on how the benefits and costs of American offshore infrastructure should be assessed and allocated fairly will be key. The Department of Energy’s recently announced “Building a Better Grid Initiative” may provide an opportunity for such coordinated efforts. By building the ability to extend offshore infrastructure, it is possible to shorten the required planning horizon for future projects – but it will take forward-looking up-front investment and planning to ensure future flexibility.

A pre-requisite for building coordinated extendable offshore transmission infrastructure is that transmission links which are developed at different locations and times are physically compatible and functionally interoperable. This requires the adoption of standardized system ratings such as voltage level, the development of an HVDC system grid code, and a solution to today’s multi-vendor interoperability challenges. Introducing further standardization will have the additional benefit of lowering the barrier to entry to new market participants, widening today’s limited supply chain.

The energy sector undoubtedly plays a crucial role in accomplishing the 1.5 C° climate change threshold target, and offshore wind energy is expected to be a major contributor to the energy transition. Many regional and global experts see the planned offshore grid as a way forward, but this solution, as do all, presents advantages, challenges, and complexities.

To learn more about this critical topic, join DNV and U.S. offshore transmission developer, Anbaric, next Tuesday, January 25th at 2 PM ET for an ACP-hosted webinar: “Planned Offshore Grid – An American Dream Come True.” Our expert industry panel will provide attendees with a deep dive into the offshore grid concept to understand how it can unlock the transition to a clean, reliable and affordable energy future in the U.S. Register for the complimentary webinar here.

This is a guest blog post from ACP member DNV.? To learn more information on how to become an ACP member, please visit?our membership page.??

Author:

Cornelis PletPrincipal ConsultantDNV