David Throgmorton was ready for an energy boom in 2008. He bought vocational training kits for high school and middle school students. He helped establish a festival to promote a new energy future. He even preached a new tomorrow to grade school students.

But here in Carbon County, where fossil fuels once were king, Throgmorton wasn’t ecstatic about a new oil play, gas deposit or coal mine. He was excited about wind.

“We easily had two classes of high school students, two successive classes of graduating high school students, who were convinced wind power was going to be their future,” said Throgmorton, director of the Carbon County Higher Education Center.

That was the year Power Company of Wyoming, a subsidiary of the Anschutz Corp., announced plans to build south of Rawlins the largest onshore wind farm in the United States.

Many local officials were ecstatic. Carbon County long ago became a misnomer in this desolate stretch of central Wyoming, where the last coal mines closed in the 1980s and the main sign of the Shale Revolution was the frack trucks passing through on Interstate 80.

Power Company of Wyoming’s 1,000-turbine wind farm promised new jobs and tax revenues in a community where economic life revolves around the state prison and a nearly century-old refinery.

The only problem: That future has yet to materialize.

“When it didn’t come to pass, it was hard to keep the enthusiasm up,” Throgmorton said. Many of the higher education center’s students have since moved on to robotics and 3-D printing.

Eight years on, Power Company of Wyoming’s plans remain a testament to the potential and the challenges of transforming America’s top coal-producing state into a wind energy leader.

The Denver-based firm is nearing the end of a laborious federal permitting process. The company has said it could begin work on a haul road and infrastructure as early as this year.

But company officials say their plans could be derailed by state lawmakers’ proposal to raise Wyoming’s wind production tax. Legislators say raising the tax could help stem a $600 million revenue shortfall, but Power Company of Wyoming representatives warn higher taxes could make the $5 billion project economically unfeasible.

“If you asked does Wyoming, A, support wind or, B, hate wind, you’d have to say B,” said former Wyoming Infrastructure Authority Director Loyd Drain, who now consults for a Venezuelan wind developer seeking to build an 840-megawatt wind farm near Medicine Bow. “It’s so shortsighted. We could have more wind development than we have today had we not tried to drive wind out of the state.”

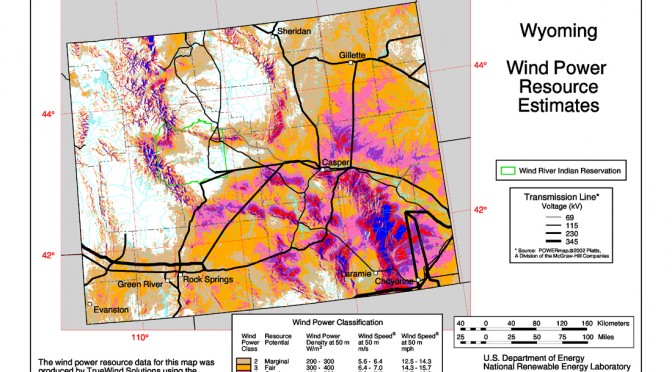

The National Renewable Energy Lab estimates that 50 percent of the best winds in the continental U.S. are in the Cowboy State. In stretches of south-central Wyoming, where Power Company of Wyoming has proposed erecting 1,000 turbines, the average annual wind speed can reach 26 miles per hour.

Yet no new wind capacity has been installed here since 2010, even as wind installations boomed nationally. A lack of transmission capacity has hindered new development in Wyoming. Permitting facilities on public land takes years. And there is this: Many in Wyoming simply do not like the sight of windmills or what they represent — a transition away from the fossil fuels that have long powered the state.

Nevertheless, there are tentative signs of a wind boom here.

Viridis Eolia Corp., the Venezuelan developer, expects to bring 30 megawatts of new wind power online in Carbon County next year. The first stage of development is on private land. Viridis hopes to have 160 megawatts of power up and running on state land by 2019 and the remainder of the project, which is on federal land, operational by 2022.

A Chicago-based company has proposed building a 120-megawatt facility to the west in Uinta County while a Salt Lake City-based developer began erecting turbines for an 80-megawatt facility outside Glenrock this summer.

Still, danger abounds for would-be wind developers. Viridis and Power Company of Wyoming are at least partially reliant on transmission lines that have yet to be built. Transwest Express, another Anschutz subsidiary, is in the ninth year of permitting its proposed 730-mile line connecting Power Company of Wyoming’s wind farm in Wyoming to southern Nevada. A final decision on that transmission line is expected in the third quarter.

And neither development has yet to ink a deal to sell its power to a utility.

“There are great opportunities, but probably we’re going to have to compete for them,” said Robert Godby, a professor of energy economics at the University of Wyoming. Other states are pushing wind development, he noted, while technological advancements have helped turbines become more efficient at lower wind speeds, undermining Wyoming’s competitive advantage.

“Assuming they’ll just show up here is probably being too optimistic,” Godby said. “You’re going to need state action and support, and unfortunately Wyoming has been lukewarm to the sorts of efforts that would be needed. Everything from a transmission effort to a renewable generation industry, and then finally tax policies.”

The debate comes at an especially fraught time for the state. Unemployment is at its highest level since the Great Recession. The mining industry, which includes oil and gas, shed 5,500 jobs between the first quarters of 2015 and 2016. State economists reckon the 55 percent contraction in taxable energy sales over that period represents the greatest year-over-year drop in Wyoming’s history.

An expansion of Wyoming’s nascent wind industry could help limit those losses but is unlikely to ever provide the employment and tax base of fossil fuels, analysts say.

In 2014, the state’s coal sector employed more than 6,000 people and contributed roughly $1 billion in annual tax revenues.

The wind projects proposed by Power Company of Wyoming and Viridis would triple Wyoming’s wind capacity to about 5,400 megawatts, or enough to power around 1.6 million homes.

Together they would create 5,000 jobs during construction and around 200 permanent positions, according to Godby’s estimates. Power Company of Wyoming expects to generate $780.5 million in tax revenues over the project’s 20-year-life span.

Even renewables’ most ardent backers acknowledge the limitations of what the industry can offer the state.

“I will tell you up front, it will be a significant contribution but it will never be anything that approaches the extractive industries like oil and gas and coal,” said Bill Miller, president and CEO of Power Company of Wyoming.

Gov. Matt Mead, in hopes of spurring additional job creation, has listed the recruitment of turbine manufacturers as one of his leading policy initiatives. But it remains an open question whether Wyoming could entice such a business to the state.

While the scale of Wyoming’s wind projects might be large enough to attract renewable manufacturing, analysts say, turbine builders have already set up shop along Colorado’s Front Range.

Vestas, a Danish turbine manufacturer, now employs 3,100 people at its three locations along the Front Range.

“Our project, if it were the only one, is still a large project. But 50 miles south of the border you’ve got a major manufacturer that wouldn’t need to duplicate anything in Wyoming,” Miller said. “You look at the other major manufacturers, they’ve got their other facilities already established. Unless you’re going to see a huge amount of growth in Wyoming, I can’t imagine anybody establishing a manufacturing facility here.”

On the Overland Trail Ranch, the rolling stretch of high prairie where Power Company of Wyoming has proposed its project, there are few signs of the planned wind farm. A fence line flickered with fluorescent ticker tape, part of the company’s efforts to reduce sage grouse deaths. A smattering of meteorological towers that once gauged wind speed and direction remain. Eight years of data collection have already produced a comprehensive wind map of the area. Grazing cattle are the most common sight.

But back at the Carbon County Higher Education Center, David Throgmorton is gearing up once again to teach students the skills needed to service the future towers.

The program essentially amounts to training electricians, the main difference being a wind technician needs to employ the same skills “at 300 feet with the wind blowing,” Throgmorton said.

The higher education center director remains as enthusiastic as ever over wind’s prospects here. He believes the new jobs will help keep young people who love Carbon County’s open spaces and its hunting and fishing opportunities from moving away. He also believes this is Wyoming’s chance to play a role in America’s new energy economy.

But he also fears that Wyoming may miss its chance. America is in a wind boom. If the state fails to act now, Throgmorton said, the opportunity may pass it by.

Benjamin Storrow Star-Tribune

http://trib.com